Languages used in medieval documents

Three main languages were in use in England in the later medieval period – Middle English, Anglo-Norman (or French) and Latin. Authors made choices about which one to use, and often used more than one language in the same document. Eventually English emerged as the standard literary medium, but it was not until the eighteenth century that Latin disappeared from legal documents.

Hebrew and Aramaic were used by the medieval Jewish community in England.

Anglo-Norman

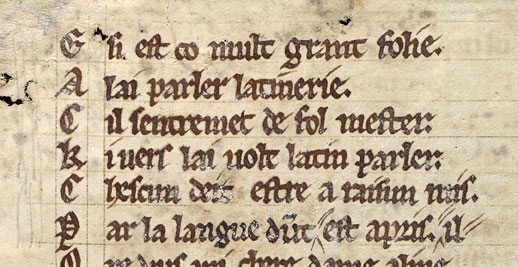

Anglo-Norman had emerged as a distinct dialect of French after the Norman Conquest in 1066 established a French-speaking aristocracy in English. It was still dominant in the mid-thirteenth century when Robert of Gretham wrote his advice on moral conduct, the Mirur. For Robert the appropriate language for lay education was French, but by the late fourteenth century his book had been translated into English.

Detail from Robert of Gretham, Mirur, in Anglo-Norman (WLC/LM/4, f.57v)

Middle English

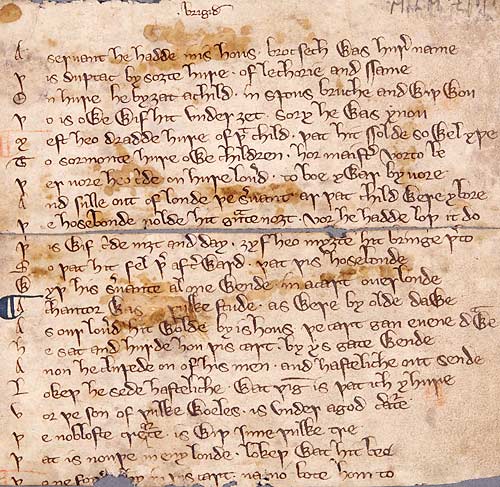

The earliest literary document in English in the University of Nottingham’s collections is a fragment from the life of St Bridget, from the South English Legendary, composed in the late thirteenth century. The scribe uses the Anglo-Saxon letters ‘yogh’ for ‘y’ or ‘g’ (ȝ) and thorn for ‘th’ (þ). He leaves a wide gap between the first capital letter of each line and the rest of the word.

See the words ‘This’ ('Þ is') at the start of line 2, and ‘begat’ ('byȝat') in the middle of line 3.

Fragment of the Life of St Bridget, in English (WLC/LM/38)

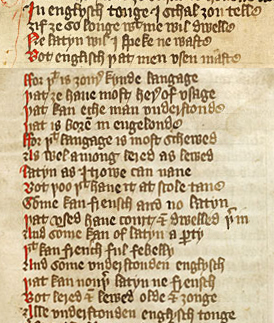

The author of the Speculum Vitae (The Mirror of Life), writing late in the fourteenth century, chose to use English and explained why.

Detail from Speculum Vitae, WLC/LM/9, ff. 1v-2r

|

In englysch tonge I schal you telle

Yif ye so longe with me wil dwelle

Ne latyn wil I speke ne waste

Bot englisch that men usen maste

For that is youre kynde langage

That ye have most here of usage

That kan eche man understonde

That is boren in engelonde

For that langage is most schewed

As wel among lered as lewed

Latyn as I trowe can nane

Bot thoo that have it at scole tane

Somme kan frensch and no latyn

That used have court and dwelled therin

And somme kan of latyn a party

That kan frensch ful febelly

And somme understonden englysch

That kan nouther latyn ne frensch

Bot lered and lewed olde and yonge

Alle understonden englysch tonge

|

I’ll tell you in English

If you’ll stay with me long enough.

I won’t speak or waste Latin,

But I’ll speak English, that people use most,

Since that is your native language

That you have most in use here,

Which each person can understand

Who was born in England.

For that language is most in evidence

Both among the educated and the uneducated.

I believe no-one knows Latin

Unless they’ve taken it at school.

Some know French and not Latin

Who have frequented the court and lived in it.

And some know a bit of Latin

Who know French very poorly.

Some understand English

Who know neither Latin nor French.

But educated and uneducated, old and young,

All understand the English tongue.

|

His explanation concludes that everybody, both the educated (‘lered’) and unschooled (‘lewed’), old and young, can understand the English tongue. In contrast, Latin was only understood by those who learnt it at school, and French by those who attended court. These languages were used by particular communities and for specific purposes.

French

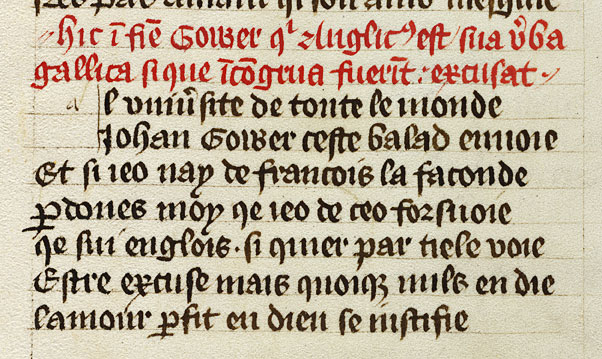

John Gower, a contemporary and friend of Geoffrey Chaucer in the late fourteenth century, wrote in all three languages. His ballades include the French poem Traitié pour les amantz marietz, promoting the virtues of married love. Shown here is a section headed by an introduction (rubricated in red ink) in which Gower apologises for any mistakes in his French. The introduction to the passage is in Latin, and reads 'Gower, qui Anglicus est, sua verba Gallica … excusat' ('Gower, who is English, makes excuse for his French words'). This followed a familiar convention of bilingual presentation. Gower’s great English work was known by its Latin title Confessio Amantis and included Latin running titles and section headings.

Detail from John Gower, Traitié ..., in French with Latin headings (WLC/LM/8, f.203v)

Although French remained familiar to Gower’s contemporaries at court and in educated or wealthy circles, the great days of Anglo-Norman as a literary medium were over. A form of French, known as 'Law French', continued to be used by English lawyers in written form until the seventeenth century. It became fossilized and degraded, because after the fourteenth century, most of those using the language did not fully understand it. Many legal terms still in existence today derive from French, such as 'attorney', 'bailiff' and 'defendant'.

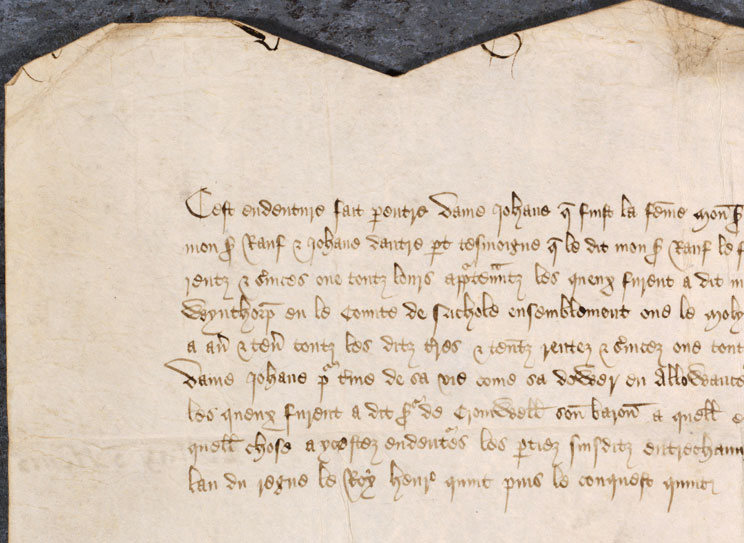

Title deeds in French are rare after the early fifteenth century. This agreement relating to dower, made in 1417 (Ne D 742), is in fact the very last French deed known to exist in the University of Nottingham’s collection.

Detail from agreement relating to dower, in French, 1417 (Ne D 742)

Latin

Latin was still the preferred language for many purposes. With its fixed grammar and spelling, it was easy to abbreviate without misunderstanding. It remained the medium for international scholarship until the seventeenth century.

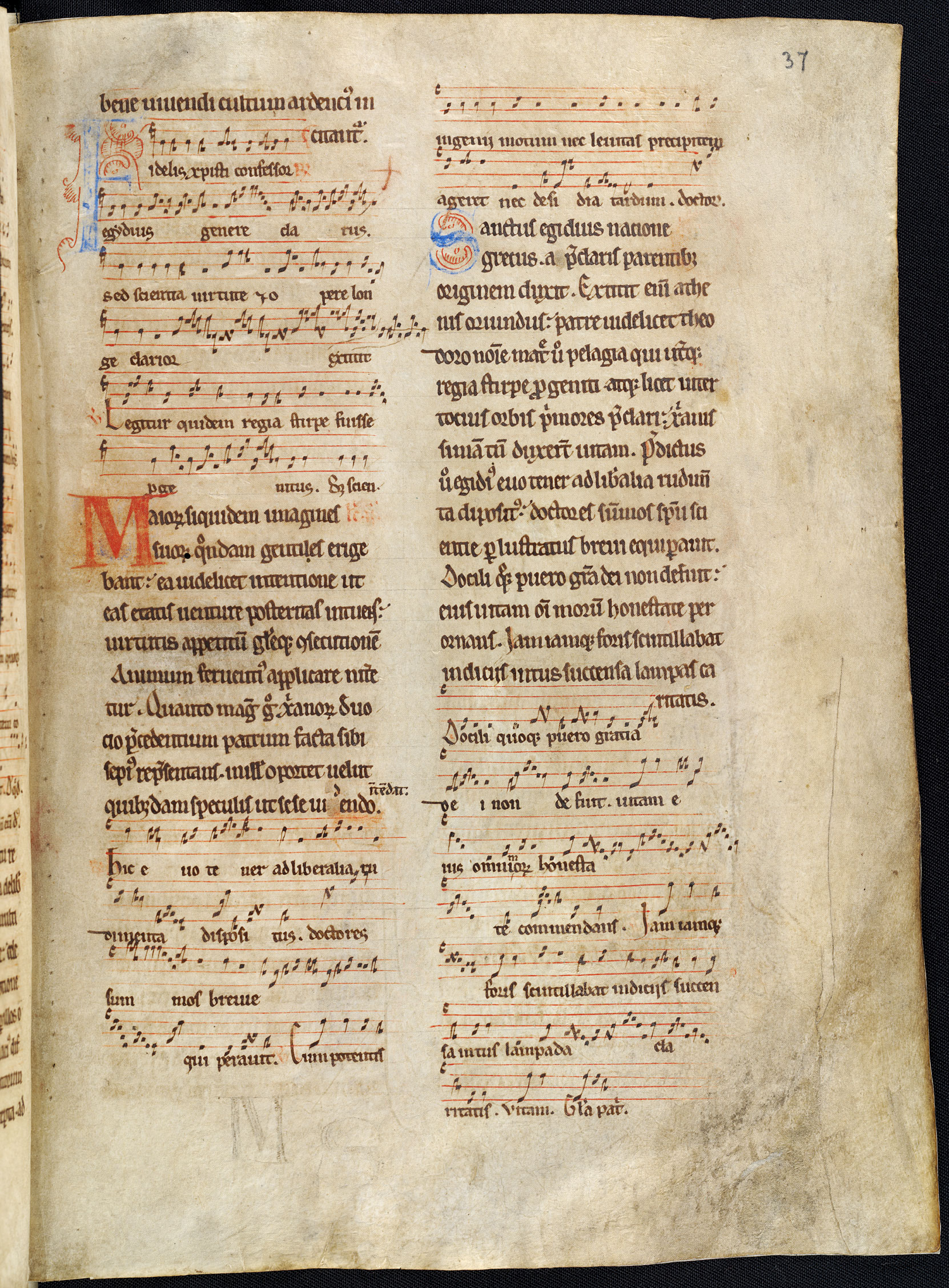

The Catholic church used Latin in its services, so all liturgical books were written in this language until the Reformation in the sixteenth century. The theologian John Wycliffe began to translate the Bible into English in the late fourteenth century, but the Lollard movement with which he was associated was persecuted by the authorities, so late medieval Bibles in English are rare.

Detail from Latin breviary with musical notation, c.1175-1225 (WLC/LM/1, f.37r)

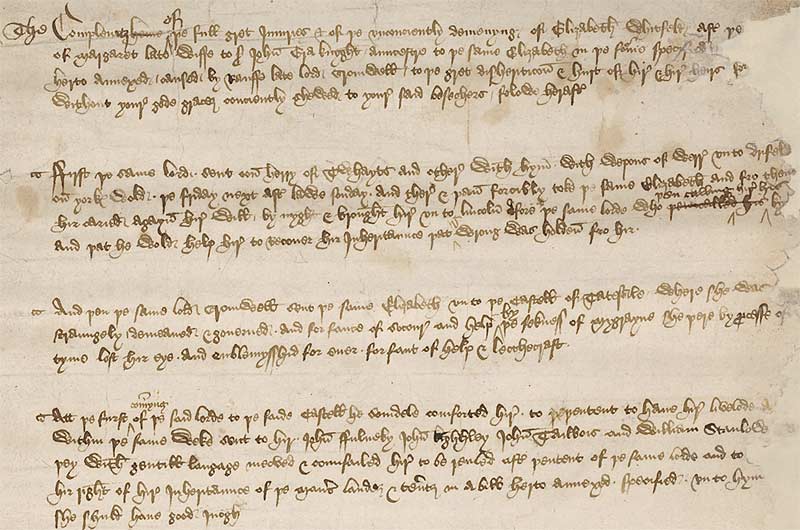

English was slow to take over as the language of government, law and bureaucracy, despite the fact that by a law passed in 1362 all legal pleadings had to be in English. This bill of complaint (Pa L 2) dates from the late fifteenth century and is indeed in English.

Detail of bill of complaint of Elizabeth Whitfield, Pa L 2

However, most other types of official document continued to be written in Latin, such as the manor court roll (MS 66/1) shown on the previous page of this unit. It was not until the mid-sixteenth century that English began to appear in manorial records, and even then it was often only used to record presentments spoken in that language at the meeting of the manor court. It was a similar situation in the records of the Nottingham Archdeaconry court. In depositions written in 1610, the words spoken by ordinary people are written in English, as they said them, but the rest of the document explaining the case is in Latin.

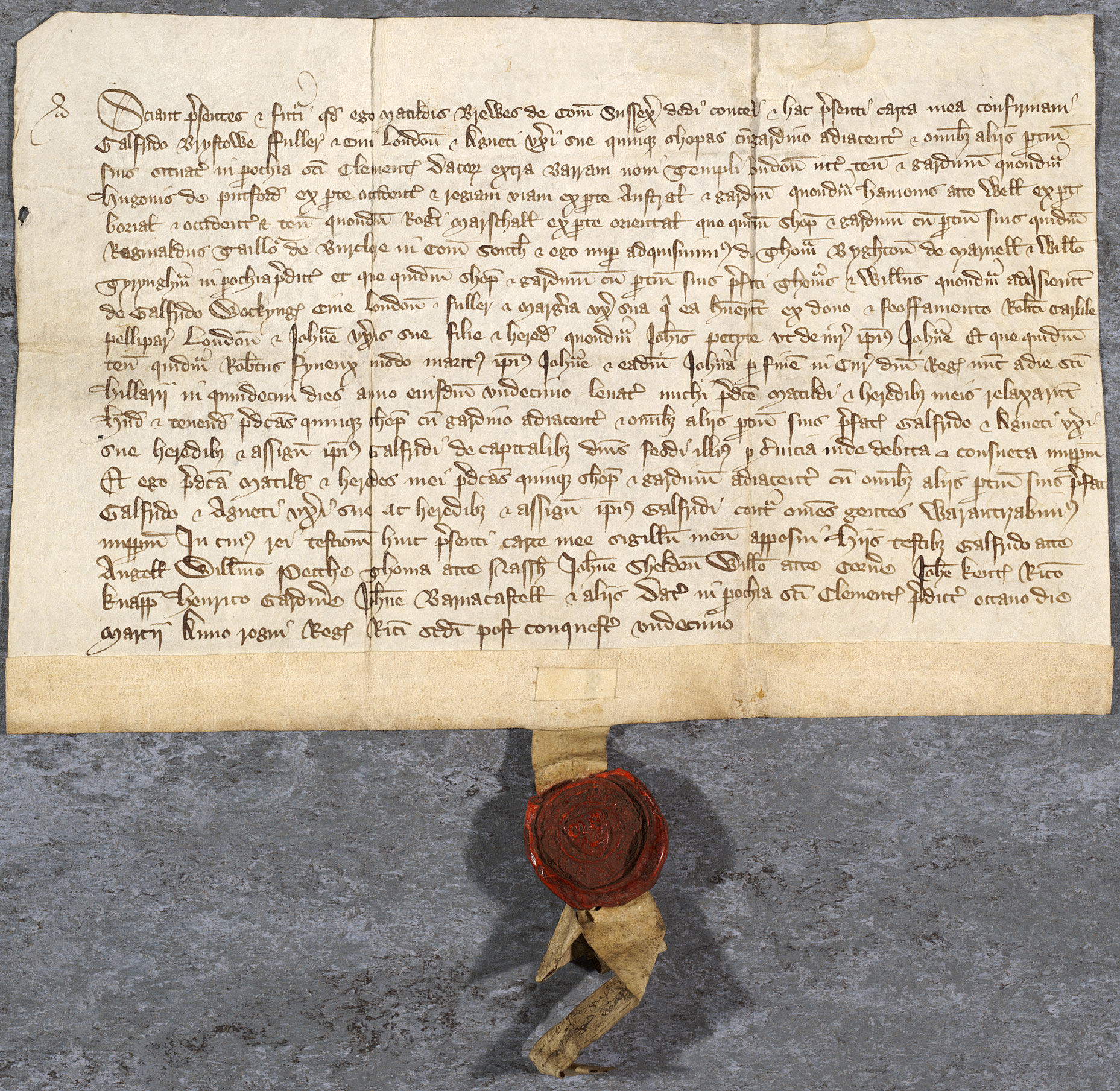

Rentals and accounts from landed estates are rare in English before the beginning of the sixteenth century. Most title deeds were also written in Latin until the sixteenth century and even later, although many fifteenth-century examples in English exist.

However, since Latin was not a living, spoken language, the scribes sometimes struggled to find suitable words and phrases to use. They often resorted to inserting English words where necessary, for instance a person's occupation in a title deed, or a description of a particular item in an inventory which could not be accurately identified using a Latin word.

Latin continued to be used as the language of some deeds and legal documents until the early eighteenth century. By Act of Parliament, 'Use of English Language in the Law Courts made Obligatory', 4 George II, c.26, 1731, it was enacted that English should be used to record all official information from 25 March 1733.

Detail from title deed in Latin, 1388, Ne D 4716

Conclusion

Researchers studying medieval documents must expect them to be in Latin or French. Even if they are in English, the medieval form of the language uses many words which are now obsolete or mean something different. However, many works of literature and some important parliamentary and governmental records have been translated into modern English and published. There are also plenty of books and websites to help researchers understand the medieval Latin used in title deeds and administrative records.

Next page: Authentication