How do we hear?

How often do we stop and think about all the sounds around us? What are the sounds made of and where are they coming from??

Try This! Can you hear the distant rush of cars on a road, birds singing or your fridge humming away? These are background sounds which we often don’t notice.

Sound moves through the air in the form of sound waves, and to ‘hear’ these waves we need something to collect and convert them to something more meaningful to us.

Our hearing system has three different parts: the outer, middle and inner ear.

The outer ear

A good example of a source of sound is a speaker, like you might find on a TV or laptop. Most speakers have a cone-shaped piece called a diaphragm which moves to create sound, and most are circular as this is an efficient shape to move the diaphragm.

The outer ear is a cone shape but much more complicated with many lines and folds, and is very good at collecting sound.

Question: in the picture above, is this a left ear or a right ear?

Sound collected by this part of the ear, also known as the pinna, travels down the ear canal to the ear drum (also known as the tympanic membrane). This all makes up the outer ear.

The middle ear

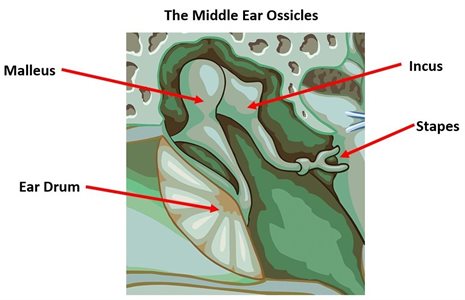

The space between the ear drum and the cochlea is called the middle ear.

The ear drum is connected to a chain of three tiny bones known as 'ossicles'. These tiny bones are the hammer (Latin: malleus), anvil (incus) and stirrup (stapes).

Did you know? The ossicles are the smallest bones in the body!

The stirrup connects to the oval window which is part of the cochlea (see below).

Diagram of the middle ear; image used with permission of Interacoustics.

The ear drum has a large surface area compared to the stirrup, so the sound energy is amplified (made bigger) as the energy from all across the ear drum falls onto the smaller stirrup; the energy is also converted from sound to mechanical energy, as the bones move and vibrate rather than make a sound.

The middle ear is ‘sealed’ from the outside by the ear drum but does need to have about the same air pressure as outside. The pressure is equalised (made the same) by the eustachian tube which connects the middle ear to back of the throat. The eustacian tube is in the bottom right of the above diagram.

Try this! Have you ever been going up or down very fast, perhaps in an aeroplane taking off or a lift in a tall building, and noticed your ears need to ‘pop’? This is due to a more rapid change in air pressure and the sensation of the air being forced through the eustachian tube. Or, if you've had a cold and your ears were sore or you couldn't hear, the eustachian tubes might have been blocked and not able to balance the pressure.

The inner ear

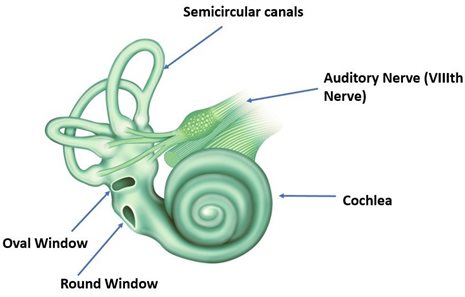

The inner ear and vestibular system; image used with permission of Interacoustics

The cochlea looks like a snail shell and is, in fact, a coiled-up tube about the size of a pea.

Connected to the cochlea are the semicircular canals which look like semicircular rings: these are part of the vestibular system, which helps us balance and be aware of our position.

Inside the cochlea there is a thin layer that runs along the whole length of the tube. This is called the basilar membrane. Along this there are many thousands of tiny hair cells: these are known as sensory receptors and they send signals to the brain along the auditory nerve.

Sound is made up of different frequencies (pitch) and these will be picked up at different strengths or intensities along the cochlea. High pitched sounds (birds singing) will be strongest towards the base of the cochlea, and lower pitched sounds (bass or deep sounds) strongest towards the top or apex.

These sound signals will be transmitted by the hair cells, which vibrate and move around, to the auditory nerve. The auditory nerve connects to a part of the brain called the auditory cortex, where the signals are ‘decoded’ into sounds we can recognise, such as speech or music.

Problems that can happen with the ear

Sometimes there are problems with the ear which we need to get help with.

Question: How do we know if our hearing is within a normal or typical range? How do we compare with other people's hearing?

Hearing tests can be carried out to check how well we can hear.

Hearing can be tested using an Audiometer, a machine that makes different sounds that are played through headphones, a bone conductor (like a headphone but sits on the bone behind the ear) or a speaker. The sounds made are normally beeps or ringing sounds that stay the same, called pure tones.

The sounds are played at a certain pitch or frequency: if the person being tested (the patient) hears the sound, they will be asked to let the tester know, perhaps by pressing a button. The tester will know that the patient can hear the sounds they are playing when they press the button. If the patient doesn’t press the button, it may mean that they cannot hear the sound. The tester then makes the sound louder in steps until the patient can hear it. Once the level of sound that can be heard in known, it is recorded as a 'threshold'. The tester will then do this again with another frequency.

Modern audiometers such as this are operated by computers.

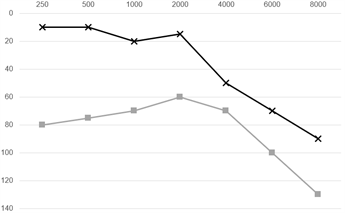

An example of an audiogram

Hearing test results are plotted onto a chart like this one:

X is the level of hearing in the left ear with headphones

Square is the level of hearing in the right ear with headphones

The Audiogram is a graph like chart that allows hearing test results to be plotted. The scale along the top is frequency, which is measured in Hertz (Hz) and the vertical scale is measured in decibels (dB).

For measurement of hearing, a special type of decibel measurement is used called Decibel Hearing Level.

Hearing tests are normally carried out by an Audiologist who specialise in hearing as well as balance diagnostics and rehabilitation work.

Find out more about audiologists

To test hearing of the quietest sounds, a special room is used.

Rooms for testing hearing usually have some sound proofing, with carpets and soft walls. These features help keep the rooms as quiet as possible to allow the person being tested to be able to hear the very quiet sounds used during a hearing test.

More about hearing loss

Hearing loss affects about 12 million people in the UK.

Find out more from RNID Hearing Loss

There are different types of hearing loss. Some are permanent, but some are temporary or can be helped with medicine or an operation by a doctor.

Permanent hearing loss

This can be caused by damage to the cochlea or nerve of hearing. Most common causes are:

- Age-related

- Genetic (inherited from your family)

- Noise-induced (long term exposure to loud sounds)

- Infection of the cochlea

People with a permanent hearing loss can often be helped to hear better by using a hearing aid.

Temporary hearing loss

Temporary hearing loss can sometimes be cured, but sometimes it can only be improved a little bit. The following are examples of problems which affect the transmission of sounds, also known as conductive hearing loss, and are often (but not always) temporary:

- Glue ear (a buildup of sticky liquid behind the ear drum)

- Perforated ear drum (where the ear drum gets a hole in it)

- Otosclerosis, where the small bones stiffen and do not move as easily as they should

- Excessive ear wax

- Infections in the ear canal or middle ear.

Most of these conditions will require treatment by a medical professional, such as a nurse, doctor or ear specialist.

Where indicated, images are used with permission from Interacoustics.

Learn more about hearing