To Have and to Hold

A number of conditions had to be fulfilled before a wedding could lawfully take place. A marriage conducted when no banns had been read and no licence obtained was classed as clandestine and was discouraged under canon law. Impediments, such a relationship by marriage or blood which was too close, or one or other of the parties being under-age, could make a marriage invalid. Religious solemnization had to take place in the parish church of one or other of the parties between the hours of 8am and 12 noon and during the reading of divine service, to ensure that all was public and above board.

There was a disparity between civil and ecclesiastical law concerning what constituted a legally binding union, which sometimes caused friction between society at large and the church authorities.

Prior to an Act of Parliament of 1645 and Lord Hardwicke's Marriage Act of 1754, all that was required was a mutual exchange of vows, usually accompanied by the gift of love tokens, in front of witnesses. It was socially acceptable for the couple to begin a sexual relationship following this betrothal. However, the Church insisted on a religious ceremony as well, and many people were presented to the church courts for the 'sin' of conceiving children before they were 'properly' married.

Because of these issues, marriage generated a rich collection of documentation, especially in the business of the Archdeaconry court, and much information about Nottinghamshire parishioners can be gathered from it.

Illustration of a marriage ceremony in C. Dibdin, The Quaker, published in The London Stage, Vol. 1 (London : published for the proprietors, by Sherwood, Jones, 1825) from PR 1243.L6 (Cambridge Drama Collection)

Marriage bonds represented the first step in a couple's application for a licence to marry. For example, William Tinker and Robert Rollingson of East Stockwith, a farmer and mariner, were bound for the princely sum of £100 to ensure that the ceremony was conducted publicly and according to law (AN/MB 59/3) - if the conditions were broken the money was forfeit.

Not surprisingly, one had to be relatively wealthy to procure such a licence, and the costs were high if it was abused. To be weighed against this, however, was the fact that a marriage by licence could take place more quickly than one by banns.

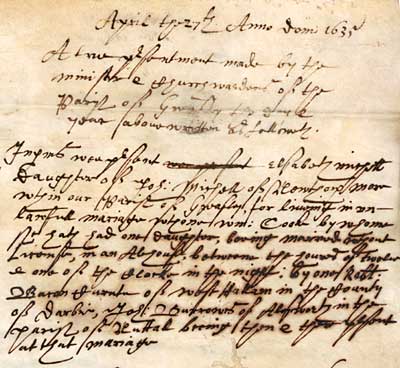

The Presentment Bill shown below, atypically written on parchment, is a good illustration of a clandestine or irregular marriage, since no banns had been read in the parish of the couple on three successive Sundays (to allow for any objection to be raised), nor had a licence been procured from the ecclesiastical court. In addition, the time and location of the ceremony, in an alehouse just after midnight, was entirely unsuitable.

The reason for the clandestine nature of the marriage is not given. However, there may have been a widespread dislike of the Vicar of Greasley, Lemuel Tuke, since the next paragraph (not shown here) refers to another irregular marriage of Greasley parishioners having taken place at Radford!

…wee p[re]sent Elsabeth Michell daughter of Joh: Michell of Newthorp more [Newthorpe Moor] w[i]thin our parish of Greasley for liueing in unlawfull mariage w[i]thone Wm: Cooke by whome she hath had one daughter, beeing married w[i]thout License, in an Alehouse, betweene the houres of twelve & one of the Clocke in the night: by one Robt. Bacon, Curate of West Hallam in the County of Darbie, Joh: Burrows of Alesworth [Awsworth] in the parish of Nuttall [Nuthall] beeing then & there p[re]sent at that mariage…

Part of a Presentment Bill relating to a clandestine marriage, Greasley parish, 1635 from AN/PB 303/710

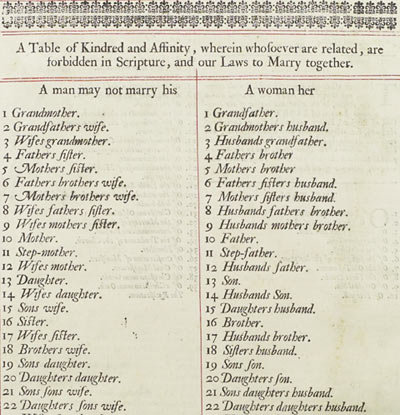

Whilst it was agreed that it was inappropriate to marry into one's blood family (brother, sister, parents, uncles, aunts etc.) due to the genetic problems this might create, it was commonly acceptable for a man to marry his sister-in-law after his wife's death, given that the two were only related by marriage.

The church courts were opposed to this on scriptural grounds and men like John Pullin of Styrrup in the parish of Blyth, who married his wife's sister in around 1596, were presented to the court for marriage within the prohibited degrees, interpreted by the church authorities as 'incest' (AN/PB 292/4/14).

Tables of 'kindred and affinity' (relation by blood and by marriage) were drawn up in the sixteenth century in an attempt to prevent these incestuous marriages, and were intended to be displayed in churches. There was periodic interest in enforcing this in the Archdeaconry, with many parishes replying in 1610 and 1630 that they lacked this important document.

Table of Kindred and Affinity, from the Book of Common Prayer (Oxford, 1681) from Mi LP 45

The marriage service in an Anglican church has not changed fundamentally since the sixteenth century. Banns still have to be called on three separate Sundays, and the traditional words can still be chosen by the bride and groom.

Illustration from the Book of Common Prayer (London : John Murray, 1845) Special Collection BX 5145.A4.E45

Next: The Physical Archive and the Conservation Challenge