By Daniel H. Mutibwa

Taking the JCNA approach to transforming places and delivering impact for local communities

An image showing the title of the event.

An image showing the title of the event.

On the early afternoon of Wednesday 26 February 2025, the Place-based Peer Learning (PBPL) Programme convened an interactive webinar.

Titled Maximise Culture's Impact: Explore the Joint Cultural Needs Assessment Approach, the webinar explored the updated Joint Cultural Needs Assessment (JCNA) Guidelines championed by Arts Council England (ACE) and the Local Government Association (LGA).

At the centre of the exploration was a seven-step JCNA approach to aligning cultural strategies with local priorities to address urgent place-based needs.

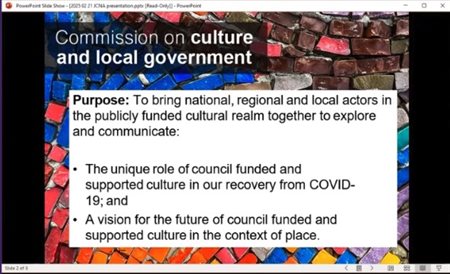

An image capturing some of the organisers and participants in attendance at the webinar.

An image capturing some of the organisers and participants in attendance at the webinar.

The webinar — which was attended by over 80 participants from across the cultural, creative, heritage, local government, and public policy sectors nation-wide — featured expert panels which provided timely and valuable insights from cultural leaders and local government professionals on delivering successful JCNAs.

The webinar also included interactive breakouts that explored how the JCNA approach can drive impact in places — including the role played by partnerships within those places.

By the end of the webinar, so much rich discussion, sharing, reflection, and learning had happened on and around how culture can be leveraged to transform local communities in places for the better to the point that there was an unmistakeable consensus that this had been a very valuable and highly successful event all round.

Ria Jones (Senior Project Manager, Place, ACE) kickstarted the webinar with some housekeeping information. Following acknowledgement of the fantastic support that her colleagues at ACE — Kate Parkin (Senior Officer, PBPL, Place-Based and Creative Ageing) and Lucy Abraham-Jones (Communications Officer, PBPL) — had provided in the run-up to the webinar, Ria gave a brief introduction — noting that the updated JCNA Guidelines were co-commissioned by ACE and LGA and published in September 2024.

Ria Jones (left in the upper row) offering introductory remarks at the start of the webinar. Professor Jonothan Neelands is right in the upper row. Louise Mitcham, a registered British Sign Language (BSL) Interpreter, is right in the lower row.

Ria Jones (left in the upper row) offering introductory remarks at the start of the webinar. Professor Jonothan Neelands is right in the upper row. Louise Mitcham, a registered British Sign Language (BSL) Interpreter, is right in the lower row.

Ria then handed over to Prof Jonothan Neelands (Professor of Creative Education, University of Warwick) who acknowledged members of his team that worked on the revised JCNA Guidelines — including Mark Scott (Research Fellow, University of Warwick).

Jonothan then gave a brief overview of the webinar — mentioning that Ian Leete (Senior Adviser, Culture, Tourism and Sport, LGA) would speak first as a champion of the JCNA and its role in facilitating investment and prosperity in places before Jonothan explored the updated JCNA Guidelines in depth.

An expert panel chaired by Val Birchall (Assistant Director for Cultural Services, Hammersmith & Fulham Council) would follow — comprising Claire Whitaker (CEO, Southampton Forward), Lisa Mallaghan (Executive Director, Bradford Producing Hub (BPH)), and Salla Virman (Head of Culture and Creative Economy, Coventry City Council). The common thread tying these panel members together, Jonothan remarked, was that they are all experienced users of the JCNA approach.

Leveraging the JCNA to facilitate thriving cultural and creative economies in places

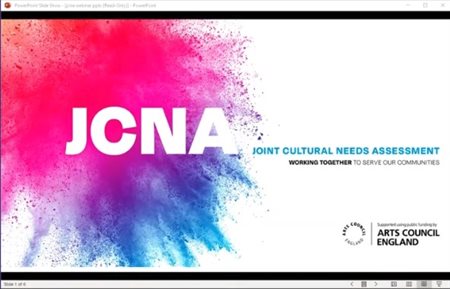

Images showing Ian Leete (LGA) and details of a piece of work that motivated the LGA to take part in the revision of the JCNA Guidelines.

Images showing Ian Leete (LGA) and details of a piece of work that motivated the LGA to take part in the revision of the JCNA Guidelines.

In his contribution, Ian Leete explained the motivation for LGA involvement in the updating of the JCNA Guidelines. He mentioned LGA’s 2022 commission on culture and local government that brought together national, regional, and local actors in the publicly funded cultural realm to harness culture to support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and — through business and development work — to assist freelancers, cultural organisations and the creative industries in places to enhance local cultural provision. This work identified four recommendations that are essential to creating a thriving cultural and creative economy:

- Capacity and resilience in place (targeting regional inequalities and delivering meaningful place-based strategies for culture);

- Leadership and power (shift towards place-based approaches that enable a greater diversity of stakeholders to shape local decision-making);

- Funding (delivery of place-based strategies using a coherent and transparent approach to funding culture); and

- Evidence (a coordinated approach to developing an effective evidence base for culture and place to measure value and shape future investment).

In relation to how the JCNA supports investment, resource allocations, and evidencing effectiveness, Ian then discussed the set of criteria that guide Central Government spending allocations to invest in a place. These criteria help to ensure that funds are well spent, that agreed objectives are met, and that there is evidence to support effective spending and successful outcomes.

Ian noted that this aligns with the overarching objective of the JCNA Guidelines to support places to think through how they are (1) allocating resources; (2) evidencing effectiveness and success; and (3) working together in the capacity of place stakeholder teams to achieve set targets.

This approach enables Central Government to justify investment in, and funding allocations to, places in Parliament based on the following criteria:

- Evidence of need and of impact (making a case for how culture is going to address need in a place — drawing on standardised metrics stipulated by the Treasury to evaluate effectiveness. The JCNA Guidelines are more attuned to the circumstances within the cultural, creative, and heritage sectors as is the Culture and Heritage Capital Approach produced by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport)

- Evidence of prioritisation (identifying what is going to make the biggest impact in a place);

- Demonstrable community and business support or engagement (approaching and addressing the needs of a place through partnership working);

- Coordination; and

- Assurance and scrutiny (holding place partnerships and their spending to account).

Some further key points made in Ian’s contribution revolved around how local stakeholders in places can make effective use of the JCNA Guidelines to maximise the impact of culture through:

- developing a good ability to articulate what culture is going to achieve for places;

- knowing when and how to engage with local authorities;

- thinking through how best to marshal the longer-term place-based funding recently announced by the current Government into initiatives and interventions that transform places sustainably; and

- preparing for what the future of devolution and local government reorganisation might look like for individual places.

The JCNA backstory, its non-statutory status, and the value of partnership working

Following Ian’s contribution, Jonothan emphasised that the JCNA Guidelines are designed to respond to the priorities, objectives, recommendations, and funding criteria mentioned in Ian’s talk, something that involves moving culture from the side table to the top table of local government in addressing place-based needs.

Images showing Professor Jonothan Neelands exploring the revised JCNA Guidelines in depth.

Images showing Professor Jonothan Neelands exploring the revised JCNA Guidelines in depth.

Jonothan spoke to the origins of the JCNA — explaining that it was appropriated from the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA). The JSNA requires local authorities by statute to work together across several public realms such as public health, education, housing, and safety to address needs based on evidence.

Although culture is not included, it can contribute to addressing needs in the said realms — and several others.

The JCNA emerged from this context to explicitly foreground the contribution of culture to responding collaboratively to place-based needs — the only key difference being that the JCNA is not statutory.

Put differently, the JCNA applies the principles and processes of the JSNA to cultural needs without statutory responsibility.

A key feature of the JCNA, Jonothan explained, is partnership working in the delivery of outcomes within an ecosystem. Central to this ecosystem approach is the importance of articulating a realistic and achievable ambition of a place in a strong and compelling manner that enables diverse stakeholders to unify behind it on the understanding that no single stakeholder can achieve that ambition on their own.

An achievable ambition is one that arises from a needs-based analysis, consultation, and co-creation with multiple stakeholders.

Besides the many opportunities afforded by effective collaboration, partnership working is naturally characterised by challenges around ways of communicating, forming and maintaining relationships, ensuring inclusivity, resourcing collaborative activities, sustaining the ecosystem and momentum over time, and managing change in plans and in partners.

The Seven-step JCNA Plan

Jonothan then discussed the Seven-step Plan at the heart of the JCNA:

- Place narrative, vision and profile (what makes a place utterly distinctive? What do the place demographics look like? What are the interests, needs, and challenges in the place? What do stakeholders want the place to become over time?)

- Place outcomes (what are the broader outcomes that a place partnership is working towards achieving? These need not be cultural at first, but could relate to public health, education, social welfare, and safety. An audit could be conducted whereby cultural outcomes can be identified and a determination made as to how those cultural outcomes can distinctively contribute to achieving the wider place outcomes)

- Cultural resources and capacity (the scarcity of resources and capacity dictates that areas of strongest need must be prioritised. A focus of limited resources on a set of realistic outcomes offers the best way forward)

- Cultural outcomes and Key Performing Indicators (KPIs) (considering limited resources, what can culture and heritage organisations, assets and services do to support place outcomes? What indicators will be used to determine whether the outcomes have been successful?)

- Cultural outputs and KPIs (what products, services and experiences will contribute to realising the cultural outcomes and how will they be measured and learnt from?)

- Activities (what cultural and non-cultural activities are needed to produce the outputs and who is responsible for the activities?)

- Monitoring and evaluation strategy (what methods and sources will be used to collect data at different stages of the process of monitoring and evaluating progress?)

The JCNA approach and its action research-based roots

To illustrate the JCNA approach in action, Jonothan reported on the experience gained at Coventry. In a bid to align cultural outcomes with the wider city place-based considerations, the ‘One Coventry Plan’ was created to take a place-based approach to tackling inequalities within local communities. One crucial driving question here was how the cultural ecosystem could contribute to this wider place-based overarching objective of Coventry as a city.

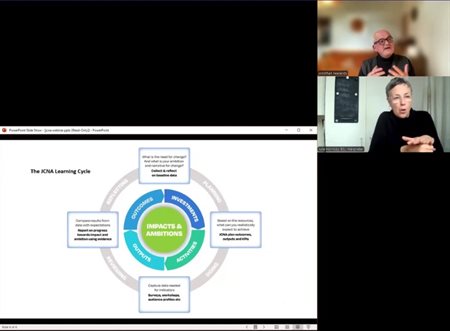

Professor Neelands discussing the JCNA Learning Cycle as a tool for taking stock, learning, reflection, and action.

Professor Neelands discussing the JCNA Learning Cycle as a tool for taking stock, learning, reflection, and action.

It is at this point that Jonothan introduced the JCNA Learning Cycle — stressing that applying the JCNA approach meaningfully and effectively goes beyond merely crafting objectives to consider how and what to learn from the JCNA Guidelines and associated processes.

The JCNA model follows the practice of action-based research which involves 4 steps, namely (1) planning (2) doing (3) reviewing, and (4) reflecting. The model starts off with identifying the need, ambition, and narrative for change based on evidence, availability of resources, and a clear understanding of what can be realistically achieved.

During the operation of the model, it is imperative to capture what works, what does not work and why, and what needs changing. Here, identifying the challenges faced informs ways of adapting.

Reviewing and reflection focus on comparing outcomes with set targets and determining — guided by evidence — whether expectations were met or even exceeded or not met at all — and why.

JCNA user experience from selected places

Image showing Val Birchall (left in lower row) introducing members of the expert panel: Lisa Mallaghan (middle, upper row), Salla Virman (right, upper row), and Claire Whitaker (right, lower row).

Image showing Val Birchall (left in lower row) introducing members of the expert panel: Lisa Mallaghan (middle, upper row), Salla Virman (right, upper row), and Claire Whitaker (right, lower row). Image capturing members of the expert panel shortly before making their individual contributions.

Image capturing members of the expert panel shortly before making their individual contributions.

Participants were then sent into breakout groups to discuss their learning until that point and to reflect on what their takeaways were.

In the breakout group I was assigned with a senior theatre practitioner and two local authority senior leaders, the key learning point revolved around the introduction of devolution and associated opportunities but also the challenges that this presents in leveraging culture for place transformation. Breakout group discussion was followed by the expert panel led by Val Birchal

Val Birchall interestingly opened expert panel discussion by picking up on the point about local government reorganisation and devolution — reflecting on how best to reposition culture to contribute to place-based objectives considering how overly different places are in terms of scale, demographics, partnerships and networks (where they exist), and capacity.

Val noted that it is important to acknowledge that places are all at different starting points. With this in mind, Val invited the 3 panel members from Southampton, Bradford, and Coventry to share their experiences of applying and using the JCNA approach — including speaking to its strengths and how its operationalisation could be applied in other contexts.

Southampton’s JCNA journey and the UK City of Culture bid

Claire Whitaker (Southampton Forward) noted that the remit of her organisation is to deliver cultural events, tourism, and cultural regeneration in close collaboration with city stakeholders and Southampton City Council. Claire remarked that the JCNA was very helpful in putting together Southampton’s bid for UK City of Culture. And although the bid was unsuccessful, the JCNA (1) informed and underpinned the work undertaken; and (2) reinforced the value of partnership working in a political context in Southampton where political leadership has not been stable enough to enable the creation of a clear and long-term vision for the city.

Claire Whitaker sharing her experience of applying and using the JCNA approach in Southampton.

Claire Whitaker sharing her experience of applying and using the JCNA approach in Southampton.

Southampton’s JCNA focuses on 5 areas:

- showcasing the diversity of the city — including telling hidden stories about the city (e.g., retelling the story of Jane Austen who lived in the city thrice);

- capacity building;

- history and heritage (i.e., harnessing heritage assets to revitalise tourism which has been inexistent since 2011);

- highlighting green spaces and waterfront; and

- supporting the development of young people.

Claire added that the JCNA is also being used to support impact investing whereby investments in culture, heritage, and tourism are being made to achieve social and environmental benefits while also generating profit — all of which contributes to addressing the city’s broader needs.

Bradford’s JCNA journey and ‘Culture is Our Plan’

Lisa Mallaghan (Bradford Producing Hub (BPH)) recounted that BPH was founded in 2019 as an ACE initiative and was one of the first pilots of the JCNA that same year. At the time, the JCNA was run by a consortium comprising 6 small arts organisations, pointing to the limited arts and cultural infrastructure that characterised the city back then. This, Lisa recounted further, made the JCNA journey at Bradford different from other places with larger scales and more resources.

When applying the JCNA approach, BPH and partners took an arts-based, inclusive approach to addressing city-wide needs involving public health, education, and social development — culminating in the publication of a JCNA report that laid out the vision of the city. Bradford Metropolitan District Council embedded the JCNA report in its strategic development agenda as part of the bid for the UK City of Culture. The JCNA vision and mission were also embedded in ‘Culture is Our Plan’ — which is Bradford’s ten-year cultural strategy (2021–2031) whose overarching objective is to leverage culture to contribute meaningfully to addressing the broader place-based needs within Bradford District.

Lisa Mallaghan sharing her experience of applying and using the JCNA approach in Bradford.

Lisa Mallaghan sharing her experience of applying and using the JCNA approach in Bradford.

Using the JCNA in this way has enabled BPH and partners to make decisions and deliver change confidently based on evidence and needs analysis emerging from research and wide local community consultation.

Ultimately, Lisa reported, the application of the JCNA in this way has led to seismic change and growth in Bradford — reinforcing the importance of remaining place-based and needs-led. Having been in operation since 2021, the JCNA will be reviewed in 2026 to identify what has worked, what has not quite worked, what has been achieved, which priorities have changed, and what might need adapting.

Coventry’s JCNA journey and the ‘One Coventry Plan’

Salla Virman (Coventry City Council) noted that Coventry’s JCNA journey has been different from the journeys undertaken in Southampton and Bradford. The introduction of the JCNA coincided with three critical moments. First, the city’s ten-year cultural strategy (2017–2027) was approaching review and a much-needed refresh. Second, Coventry’s status as UK City of Culture (UK CoC) (2021–2025) had produced huge amounts of data on cultural engagement and participation but it was not immediately clear what use these data would be put to. Third, the city was in the process of setting up a Cultural Compact.

Salla narrated that Coventry City Council’s high-level understanding of the power of the arts, culture and heritage in addressing place-based needs informed the step of leveraging the large UK CoC data sets to maintain high-level engagement with, and participation in, culture across the city. To help maintain that momentum effectively, the JCNA was introduced. Not only did this help the Council to take stock, but also evidence how its arts and cultural provision as a non-statutory service continued to contribute to the place-based objectives of the city. This was done by linking arts and culture to the city’s ‘One Coventry Plan’ (2022-2030) which sets out the city’s vision and priorities.

Salla Virman sharing her experience of applying and using the JCNA approach in Coventry.

Salla Virman sharing her experience of applying and using the JCNA approach in Coventry.

The Council took the JCNA themes and applied them to the KPIs of the organisations it funds to be able to justify spending and investment against the outcomes that the funded organisations deliver. The JCNA will be aligned with the cultural strategy following the planned refresh but for now — it has already played a crucial role in helping to form a place partnership consisting of the Council, Cultural Compact, residents, local community organisations, small arts organisations, and freelancers.

It remains to be seen how the momentum will be maintained in an environment where the city and its people, politics, finances, and policies are constantly changing.

Following Salla’s presentation, a Q&A session followed — guided by the following key questions:

- What skills, capacity, and resources are needed in places to make the JCNA work?

- What governance models for places are there and how have they worked based on panel members’ experiences?

- What was the (social) return on investment following application of the JCNA?

Skills, capacity, and resources needed to make the JCNA work

In Southampton, Claire Whitaker noted that the JCNA approach provided a clear roadmap following the end of the city’s UK CoC bid. This enabled resource to be ringfenced to support the development of several 5-10-year strategies including:

- the Heritage Strategy;

- the Destination Management Partnership;

- the Cultural Strategy; and

- the Festival and Events Strategy.

Some of this work was supported by a research university partner, something that had not happened previously. Having been designated as a priority area for devolution, the city is considering what this means for its position, place-based objectives, and knowledge base in a broader geographical area. The delivery of outcomes identified by the JCNA approach has thrived on extensive community consultation in fora and spaces that already exist and are active as opposed to starting from scratch. Proceeding this way has allowed for outcomes to be achieved on less resource.

To work around limited resource in the process of developing a needs analysis as part of the JCNA approach in Bradford, Lisa Mallaghan commented that ‘Bradford Pools’ were set up to bring together and marshal resources, people, knowledge, and experiences into the delivery of action research-based activities. These activities were led by artists and cultural practitioners that convened new and existing, diverse community groups — generating a wide range of artefacts ranging from a radio podcast to poems to illustrated maps that captured creative responses to some of Bradford’s lived experiences and stories. These artefacts were then thematically analysed by expert consultants and the contents written up in a JCNA report. This underscored the significance of inviting diverse perspectives to inform a more rounded and diverse approach to engaging with place-based experiences and needs.

Salla Virman noted that Coventry City Council is among some of the local authorities that still run the Household Survey which provides very detailed local data on cultural engagement and participation among other things. She noted further that although these data are a very valuable asset to work with, it is important not to rely too much on data. She also remarked that although community consultation is often useful, too much of it with no action is counterproductive. Salla also talked about the importance of engaging with the JCNA Guidelines and developing/refreshing cultural strategies as a vital process as opposed to interacting with them merely as documents.

Governance models for places and experiences of their effectiveness (or lack thereof)

Lisa spoke of a shift in power in Bradford whereby culture has been moved from the sidelines and consciously made the focus of discussions. A case in point is how BPH has embedded a needs-led approach in its work — conducting needs analyses on various cultural subsectors (e.g., dance) but also with various communities of interest and practice (e.g., LGBTQIA+ creative practitioners). She stressed how frustrating it is that culture is compelled to make its case repeatedly because the arts and cultural sector is not on the central agenda. She sees a danger in the quest for the JSNA and JCNA to instrumentalise culture to support other identified needs and issues. This, in Lisa’s view, could lead to forgetting about the existence of culture in its own right. Salla stated that the triangulation of the JCNA with the cultural strategy and Cultural Compact work justifies the existence of Coventry City Council among other things.

Lisa Mallaghan discussing the shift in power in Bradford where culture has moved from the sidelines to the focal point of discussions in the city while at the same time cautioning against its instrumentalisation.

Lisa Mallaghan discussing the shift in power in Bradford where culture has moved from the sidelines to the focal point of discussions in the city while at the same time cautioning against its instrumentalisation.

Salla Virman underscoring the importance of triangulating the JCNA approach with cultural strategy and Cultural Compact work to address place-based needs effectively.

Salla Virman underscoring the importance of triangulating the JCNA approach with cultural strategy and Cultural Compact work to address place-based needs effectively.

JCNA return on investment, the process of its implementation, and the creation of a cultural sector plan

A key point noted here was that investment in the JCNA can attract further investment but tracking actual figures in pounds may not be straightforward. In Bradford, the return on investment was £7,000 but other kinds of value derived were far greater as Lisa Mallaghan demonstrated above. A central strength of the JCNA approach is helping to identify what resource a place has at its disposal and how this then is utilised in the most efficient way to achieve set objectives. At this point during the webinar, there was still time for a second round of breakout group discussion and concluding remarks. In my breakout group with the senior theatre practitioner and two local authority senior leaders I had met earlier, discussion revolved around how the JCNA approach could feasibly work in the context of places characterised by different scales, resources, capacities, and political configurations. The value of using the Household Survey also triggered some interesting discussion.

Ian Leete (LGA) sharing concluding thoughts on approaching the process of implementing the JCNA approach.

Ian Leete (LGA) sharing concluding thoughts on approaching the process of implementing the JCNA approach.

Jonothan sharing final remarks on how to apply and use the JCNA approach in a focused and targeted way.

Jonothan sharing final remarks on how to apply and use the JCNA approach in a focused and targeted way.

In concluding remarks, Ian Leete (LGA) observed that implementing the JCNA Guidelines is time-consuming and can seem daunting at first, but that it is time well spent in the long run. He commented that it is worth approaching implementation in stages or increments and that this exercise does not have to be led by local authorities — although it is of great help if they are involved.

An image showing the moment the webinar is brought to a conclusion.

An image showing the moment the webinar is brought to a conclusion.

All in all, Ian noted, a broad coalition of willing and committed place partners is what it takes. Jonothan Neelands advised that the JCNA does not have to respond to all place outcomes. Rather, a focus on those outcomes where culture can make a distinctive contribution is sufficient.

Salla highlighted the usefulness of creating a cultural sector plan for place which can helpfully connect both non-cultural and cultural partners in ways that can develop synergies. For places such as Coventry designated as a priority area for the creative industries, such synergies can help attract investment and capital funding among other things. In this configuration, non-cultural stakeholders can be one of the greatest assets of a place.

The JCNA Guidelines and the full webinar recording can be accessed via

Maximising Culture’s Impact: Explore the Joint Cultural Needs Assessment Approach.