By Lily Roslof

In this blog post, Lily Roslof explores some fascinating, historical links that are said to have characterised the production of fashion, its marketing, androgynous dimensions, and queer features.

This research was motivated by the 'Symington "Avro" Corset Guide' that Lily photographed and digitised in the context of the Curating, Researching, Digitising and Exhibiting Leicestershire Museum Collections Placement.

In addition to offering students distinctive professional development competencies and skills coveted by graduate job employers, the Placement is also providing students with first-hand experience of working on an exciting and real-world project at the intersection of the heritage sector, the digital media industries, and local government context.

Lily Roslof is a finalist pursuing a BA in History and East European Cultural Studies. Lily expects to graduate in 2025.

Lily Roslof is a finalist pursuing a BA in History and East European Cultural Studies. Lily expects to graduate in 2025.

- My name is Lily, and I am a final year student of History and East European Cultural Studies.

- My academic interests lie in Medieval religious history which means I have a lot of experience telling people about niche historical subjects.

- My passion is making the past accessible and especially teaching others about how history is all around us.

- I ran a club in high school where I gave presentations and tours about art history with the goal of educating my peers.

- This project combines those passions for me and I'm glad to be helping Leicestershire Museum Collections become more accessible and spread the word about all the kinds of history their artefacts hold.

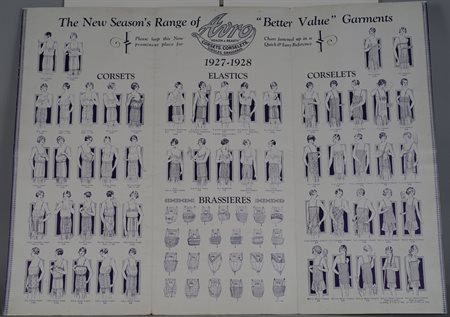

I chose the 'Symington "Avro" Corset Guide' shown below in Figure 1 which also effectively served as a corset advertisement back in the day. The reason for this choice is because of the duality of a feminine product – the corset, demonstrating the androgyny and masculinities of women’s fashion in the 1920s.

Queer history does not only encompass personal identity, but also the continuities and changes in concepts of traditional gender. This corset advertisement displays the subversion of femininity to sell its products.

It also shows how fashion trends, determined here by new interpretations of gender presentation, have guided companies and had broader social resonance.

The 1920s were a period of change in women’s fashion. Women moved away from curvaceous silhouettes seen in Victorian and Edwardian styles to the rectangular ‘flapper’ style.

The women on this ‘Avro’ corset guide are quintessentially 1920s. Depicted with short hair and trying on the products of Leicestershire corset company Symington, they embrace the androgynous fashion of this era.

Figure 1: Inner panels of unfolded Symington ‘Avro’ Corset Guide showing the 1927-1928 product range, photographed at the University of Nottingham. Image Credit: Lily Roslof.

Figure 1: Inner panels of unfolded Symington ‘Avro’ Corset Guide showing the 1927-1928 product range, photographed at the University of Nottingham. Image Credit: Lily Roslof.

The French term for the ‘flapper’ style – garçonne, is a play on the word ‘boy’, indicating both the evoked gender-presentation and youth-driven nature of the trend (Cole and Deihl, 2015, p. 136). This term encompasses why I view this corset guide as an important study of queer history.

The garçonne presents an example of historical gender subversion and how gender presentation is not actually as ‘traditional’ as it may seem. The 1920s show that femininity has changed throughout history and is not static.

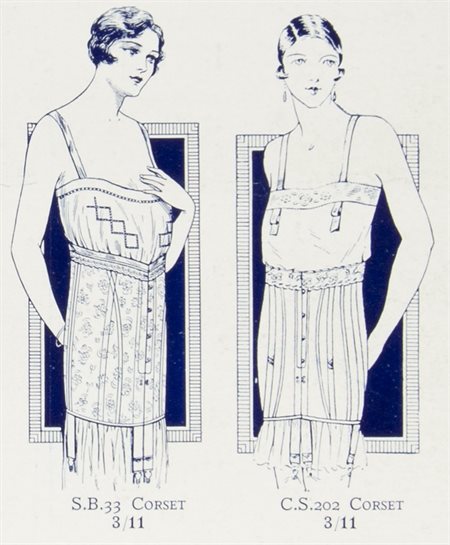

The distinct shape of the desirable ‘flapper’ altered the purpose, and therefore style, of corsets. As Figure 2 below shows on the inner-left flap, these garments were centred on the hips, going from waist to thigh.

This was a distinct shift from the popular Edwardian ‘s-shape’ corset, which focused on the hourglass shape, with a small waist and accentuated rear. The changes in the styles of corsets demonstrates the transition of femininity and female presentation.

Figure 2: Close-up from corset guide, left panel, women depicted in ‘Avro’ corsets, digitised at the University of Nottingham. Image Credit: Lily Roslof.

Figure 2: Close-up from corset guide, left panel, women depicted in ‘Avro’ corsets, digitised at the University of Nottingham. Image Credit: Lily Roslof.

Figure 3: Close-up from corset guide, right panel, women depicted in ‘Avro’ corselets, digitised at the University of Nottingham. Image Credit: Lily Roslof.

The more full-body garment, corselets, seen on the inner-right flap in Figure 3, resemble chemises and would distribute any compression evenly along the torso. They were also often boned, to assist in slimming the chest and hips and provide stability in the shape of the bodice (Corset Story, 2022). A corselet created a ‘smooth’ underlayer with a rectangular silhouette to support a ‘flapper’ style dress. Smoothing the hips in particular served a garment with a popular low, or ‘dropped’ waist (Cole and Deihl, 2015, p. 137).

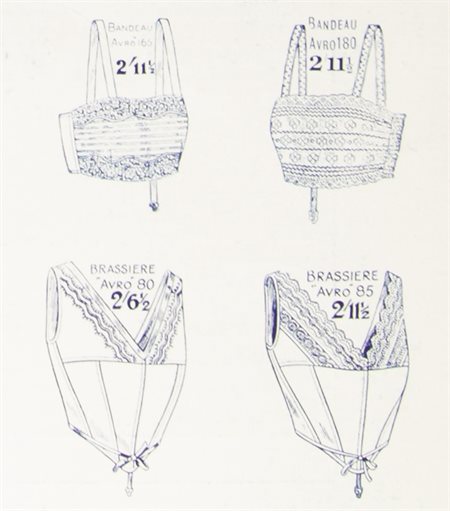

Figure 4: Close-up from corset guide, centre panel, depictions of ‘Avro’ brasseries and bandeaus, digitised at the University of Nottingham. Image Credit: Lily Roslof.

Figure 4: Close-up from corset guide, centre panel, depictions of ‘Avro’ brasseries and bandeaus, digitised at the University of Nottingham. Image Credit: Lily Roslof.

Brassieres emerged as a separate garment in the early twentieth century for women who did not need a corset for the ‘flapper’ look (Cole and Deihl, 2015, p. 142).

Advertised on the inner-centre panel, they did not have cups (‘separated’ bras came later) and were meant to contain and flatten the chest. This purpose is similar to the modern ‘binder’, which shows an interesting relationship between gender, queer and fashion history.

In comparing 1920s brassieres to binders, I believe it is reasonable to assume transgender and nonbinary people in the early-twentieth century could and would have used a brassiere in the same way.

Though I could not find evidence to support this hypothesis, for historians it can be hard to determine the intentions of masculinities in some cases because modern understandings of gender and sexuality are anachronistic to the experiences of people in the past.

Nowadays, trans and nonbinary people flatten their chests to align with their gender presentation, which is the same for ‘flapper’ women. They wanted to masculinize themselves with a brassiere, as an expression of feminine identity.

The items here show how women interacted with their bodies and appearance through fashion. By decentralizing the chest, waist and hips for a rectangular and flattened presentation, women were redefining femininity for a new age.

Nowadays, masculine-presenting women are often stereotyped as lesbian, but this association emerged at the end of the 1920s. Openness to gender presentation in this period, with the ‘flapper’ style, was associated with youth and immaturity, over an indication of sexuality.

The conversion of age and gender also makes me reflect on how early gender expectations are imposed, especially through clothes. The guide explicitly targets younger women and girls, also called maids, through the drawings and names of the products. Puberty is a particularly turbulent period for queer people, because societal expectations of sexuality and gender presentation become more prominent and create an internal and external conflict with their identity. With this guide, young women are shown that their femininity can come from masculine presentation.

One important factor in considering this corset guide is that it was an advertisement, and it instructs that it should be ‘in a prominent place’ for costumers.

For Symington, the ‘Avro’ line helped secure its popularity and legacy as a corset producer, even worldwide (Harborough Museum, n.d).

Corsets are a starkly female product, and this advertisement shows how fashion-production and marketing followed the styles of its audience.

Because it directly mentions its audience of young women, it shows they were embracing androgyny and Symington catered to their desires.

Though this corset guide does not make a direct reference to queer history, I think there are several ways to read queerness in it and reflect on historic circumstances for queer individuals.

Clothing, particularly undergarments, is a universal experience of the gender divide and expectations for presentation.

However, the 1920s demonstrate how the understanding of femininity changed to reflect androgyny and/or masculinity.

The ad targeting girls invokes questions of puberty and queer identity, and how gender was imposed on children at this time.

Making comparisons to modern ideas – like binders, or stereotypes of masculine women being lesbian – allows for considerations of continuity of queer history and where our modern ideas come from.

References