By Melissa Campbell-Oulton

In this blog post, Melissa Campbell-Oulton shares her very intriguing and instructive research on perceptions of whether women’s clothing in the past should be understood as an expression of freedom or as a vehicle for suppression. Melissa interrogates those perceptions through the lens of the relationship between the corset and Civilian Clothing 1941 (CC41) women’s trousers. Melissa digitised a selected corset using 3D digital techniques in the context of the Curating, Researching, Digitising and Exhibiting Leicestershire Museum Collections Placement. In addition to offering students distinctive professional development competencies and skills coveted by graduate job employers, the Placement is also providing students with first-hand experience of working on an exciting and real-world project at the intersection of the heritage sector, the digital media industries, and local government context.

Melissa Campbell-Oulton is a finalist in the School of Humanities. She expects to graduate in 2025..

Melissa Campbell-Oulton is a finalist in the School of Humanities. She expects to graduate in 2025..

I am a third year Philosophy and Psychology student, working on the Curating, Researching, Digitising and Exhibiting Leicestershire Museum Collections Placement. Spanning the collection, research, 3D photogrammetry and marketing of my object, I am excited to work on all-pervasive aspects involved in making Leicestershire’s archives more available to the public.

I am particularly interested in how we assimilate parts of our identity with ordinary objects, and what it means to access aspects of ourselves reminiscent of figures from the past. I worked at the University’s Digital Transformations Hub in 2023, turning local archives into public documents; I found this incredibly interesting and therapeutic.

This new project allows me to go beyond just the processing of information, to doing the research behind the significance of objects and their narratives, and how to convey this.

In my day-to-day life, I love researching family history. This is namely via photo albums or letters, some from as early as the 1890s, alongside grandparents relaying mundane details about their childhood bedroom, or their father’s first car. These conversations strengthen my present relationships, as well as providing the most direct access into family identity.

In this way, I like to engage in the more personable aspects of history - the areas that families or groups converge on, and what this means.

Clothing has been a mechanism for voicing internal conflict and identity throughout time; In times when women had little control over their roles in society, clothing became a tangible way to have autonomy in some domains. The 19th century saw the rise of fashion practices that were not only symbolic of social class but also deeply entwined with gender roles, identity, and power dynamics. Among these, the corset stands out as a symbol of both oppression and subtle forms of female resistance.

I will explore how identity has been both suppressed by clothing or served as a source of liberation. In this context, the corset is not merely a garment, but a representation of the battle between personal agency and societal restriction. It highlights the tension between conformity and individuality, submission and rebellion, private ownership of the self and the public imposition of norms.

It also suggests a form of quiet resistance - means by which women, despite their exclusion from overt avenues of power, found subtle ways to assert themselves within the bounds of an oppressive system.

Through this lens, the corset represents both a mechanism of control and a vehicle for female self-empowerment, a nuanced and multifaceted symbol that reveals a lot about the complexities of gender and power in the 19th century.

I am particularly interested in the relationship between the corset and Civilian Clothing 1941 (CC41) women’s trousers, reflecting the social process of female emancipation, class integration and transcending limits on gender expression.

I will look at how political events have had both direct and indirect implications on identity - i.e. how a war fought by women on the home front aided their integration into the workforce, normalising practical clothing, aiding in the deconstruction of the perfectly dressed wife.

From the other end, I will look at the complex history behind how petticoats served as a marker of identity, for the lady of the house, men, and housemaids.

The petticoat represented a lot for women in the 19th century. To society, it demonstrated one’s social standing and ability to maintain the family’s reputation - via the ability to keep in with current trends, often set by the most popular Lady. To men, it dichotomously maintained the fragility of the female form and their need for guidance, while also creating a mirage of the perfect, idealised woman. For the woman herself, it marked a form of self-discipline.

The tight lacing on corsets were restrictive, and often painful; The French saying ‘beauty is pain’ reflects how this discomfort became a form of control over the body, offering power in areas where women lacked control - such as employment, marriage, and education (Balin, 1905). In hindsight, the corset’s tightness and restriction reflect a broader issue of conformity to societal expectations, and the suppression of individuality, and ultimately, the self.

What corsets represented

For women, corsetry and personal design opened up a kind of social ontological conversation about identity. It served as a form of private language that was largely inaccessible - and overlooked - by men, without the access to the subtleties of what different lacing, length, or materials indicated.

This form of hiding in plain sight became a way for women to reclaim their voice. While women were excluded from academic publications and politics, they could still communicate through social interactions.

This form of ownership of the self, and silent peer understanding, marks a fine-tuned response to liberation within limits; on the one hand, it provided women a secret ownership of their body, identity, social relationships and ultimately, of language.

On the other hand, the fact that this communication was covert and hidden reflects the more pervasive issue - that men held ownership on the public ways that women presented this idea of the self.

I’m interested in this idea of a collective secret amongst women; a set of terms and protocols inaccessible to men, and women not of ‘their kind’.

This form of silent communications persists in many ways; like social faux pas that those with generational wealth might have access to, but recent members of the middle class fail to access - creating a discreet difference, that only those ‘in the know’ are astutely aware of.

In the 19th century, clothing represented much more than just who was a member of a private club, but a whole non-verbal exchange of how we perceive ourselves and how this influences social alliances, and ultimately how we want to be perceived and present our identity.

How identity differed for housemaids

The balance between self-control and submission becomes more complicated for the housemaids. On the one hand, they will also have struggled with issues of identify - in many ways facing greater internal conflicts than women of higher classes. Their identity was seated in being a member of the household, and to provide a service to those who looked like them - but with fundamentally different opportunities - different lineages and inheritances; in effect, housemaids were part of the chess pieces that maintained the image of the establishment, belonging to the estate, rather than acting of their own volition.

In this way, the struggles of control and lacing might act more as a form of small control in an otherwise very monochronic life. Interestingly, the leading narrative that housemaids served as the image of their master is incorrect; in fact, it was often the Lady of the house (in medium-sized estates) that had governance over the running, hiring and standards that the staff were obliged to maintain. In a dichotomous fashion, the Lady became liberated in one sense via a form of control, whilst other women were directly placed further into subjugation via her orders.

For the Lady of the house, tight lacing was in part a reflection of her status for its impracticality; it suggested she was not partaking in the housework, and therefore had a network of staff maintaining the estate. This posits an interesting balance between directly encouraging housemaids to be presentable and wear corsets for the image of class (externally), whilst also requiring them to be notably distinct from the upper class, and not infringing on the ‘innate’ differences between them.

An interesting reflection is whether, to any degree, this exclusion from the complex nature of female dress ware was in part a liberation. Clothing accessibility was nuanced. However, although housemaids were physically restricted from class integration, in one sense the lesser emphasis on perfect English, the intricacies of social faux-pax and airs and graces, suggest that there was less suppression of identity. While housemaids were reprimanded by their employers, their conformity was less self-imposed than that of upper-class women. Their exclusion from the narrative of perfection could, in a way, offer more freedom than the upper-class women's struggle to maintain a flawless image of wealth and class.

McClintock (1995) explores how the housemaids -or women without a workforce - engaged in a commonplace nightly ritual, rubbing hands with bacon fat and sleeping with gloves. This ritual aimed to erase the visible signs of wear from the housework in the day, in a way that could maintain the image of the gentile, attractive woman. He looks at how 'all the signs that were evident of the women's agency, especially in work related to cleaning the house, kitchen, and childcare, were carefully hidden through an outward appearance that evoked fragility', an idea that no longer marks it as self-maintenance, but instead as self-erasure (McClintock, 1995, p.152).

To a lesser degree, it mirrors opinions on anti-aging creams, or the rise in Botox to ‘wind back the clock’; on the one hand, these intentional acts highlight the physical ownership on what we do to our bodies. However, on a more systemic level, it reinstates the question why women in particular feel the need to remain youthful. Particularly in the 19th century, a period coinciding with the height of the male gaze, this control questions whether it is in fact done truly for the self, or instead, at least on some subliminal level, to fit into the male gaze, ultimately re-suppressing the true self.

In this way, although housemaids might have less access to the covert forms of self-expression, there was still this idea of self-regiment and the maintenance of being attractive (Mulvey, 1975). The idea of identity as being highly intertwined with the preservation of youth and beauty seems to transcend the classes, as an issue still highly eminent in today’s society.

Is the corset a symbol of liberation or subjugation or more of an embodiment of voyeurism and sexualisation?

Corsets, in one sense, provided a physical form of control, or subtle female communication, and of identity. Fetishized literature holds many references to corsets, as is seen in ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ and ‘Lady Audley’s Secret’ (Aspinall, 2012). This was particularly contentious in the aftermath of the ‘Obscene Publications Act of 1857’, banning the publication or distribution of ‘obscene’ texts.

This raises several questions:

- Who is fetishizing the corset?

- Is it women, drawn to the power of the female body or a queer attraction, or is it men, idealizing the fictional 'perfect' woman?

This leads to more pertinent additional questions:

- Is corsetry a form of liberation or further subjugation?

- Does it strip women of ownership over a garment not even visible in daily life?

- Or does it give women a powerful image of themselves, a demonstration of the sexual power they hold over men - something they might pine after but not attain?

However, if we consider the idea of unattainability, we have to explore yet another additional question:

- Does this create a dehumanizing narrative for women, where even in fiction, they can never live up to the ideal?

These questions are complex and ultimately hold true in many ways today - namely debates within the porn industry, or glamour images. Katie Price notoriously argued that her sexualised self-portrayal was a form of empowerment - and to shame this sexual liberation is to confine women, rather than liberate them.

This remains a contentious issue, but it shows that the sexualization of women isn't a black-and-white issue. While it may be viewed as an act of liberation, it ultimately contributes to an environment of female sexualization, creating divisions and contradictions within a community of the female experience.

The corset literally moulded the body to create a desirable image not only for men, but for female rivals, and the chasing of wealth itself. The idea of this as a mode of sexual expression is interesting.

At a time so entrenched in the repression of female sexuality, it's difficult to find a consistent narrative on how corsetry was viewed. Some condemned tight lacing due to the illusory figure it created, suggesting a disapproval of female sexualization from both men and significantly, from other women.

In this instance I think, particularly amongst younger women, there was this fantasy over a small-scale, relatively unthreatening rebellion - that ultimately incurred the wrath of family members, whilst simultaneously securing the validation of male suitors - even more fanatical if they were totally unsuitable for courting.

In one sense, this ability to intentionally play into the sexual power that the corset held, and the threat it held against breaking the carefully curated family image, gave a sense of liberation against the power dynamics that they were cornered in to.

However, in a less liberating sense, the corset 'pandered to the male gaze through pornography, and therefore was fetishized as a way to access the female body', further fuelled by societal fears of female sexualisation (Walsh, 2019, p9). Certain corsets were even coined as ‘monobosum,’ as seen in Vogue in the 1890s, due to how they pushed up the breasts while maintaining an hourglass silhouette. This increased the voyeuristic male gaze, witnessed in media outlets like the English Woman’s Domestic Magazine.

This moves the idea of being liberated from norms and familial expectations, to walking straight into the hands of further subjugation via other men. The onus of female sexualisation is placed back onto men, altering their real-world interactions, with additional sexual expectations and power over the idealised woman.

The corset’s role in shaping the sexual image of the ‘perfect woman’ is multifaceted; and the interpretation will likely have differed depending on the age and background of the 19th C audience. In some ways, the tight lacing of corsets fed into the sexual image of the ‘perfect woman’ - interestingly, an image curated and sustained more by women, but still ultimately controlled by men.

To have control of the corset was to have control of the physical image, in ways that controlling social image was harder to do, constrained by an interplay of wealth, class and ‘assets’.

Charles Reade, through his 1873 novel ‘A Simpleton’ denigrates the use of the corset - recognising it emulated the direct and indirect control on the female body; As Steele points out, the quintessentially Victorian corset became a representation of the 'creation and policing of middle-class femininity', a physical marker of inaccessibility to a woman’s own social sphere, education or daily roles (Steele, 2001, p.60).

Yet, the voyeurism engaged in by men created a sense of sexual control that women, in turn, could shape collectively. This complex dynamic allowed women to play on male desire through corsetry, providing a form of agency.

While it still undermined full control over the body, it demonstrated how there was something that men could not access purely by class or reason. Whether a woman actively engaged in tight lacing or embraced the overt sexualization of herself via the corset, the knowledge that it was an obtainable mode of control offered a form of liberation.

It symbolized a rebellious, unspoken threat that women could, if they desired, dismantle this image of the perfect chastised girl and ultimately reinvent their public image with a form of sexual control.

In this way, whilst the sexualisation of corsetry was consumed primarily by men, aiding in the unrealistic expectations within relationships, the idea that women could intentionally elicit such displays of emotional craving demonstrates a tailored form of power in the dynamic between man and woman. The evoking of emotions and the ceding to weakness and desire mirrors the very thing that women were criticised for.

I think this demonstrates an ironic regaining of power, in a domain that women could access, being the understanding and manipulation of the body. This suggests that the sexual power of the corset was not purely a form of voyeuristic submission to the male gaze, but simultaneously an expression of female sexuality and power.

The move away from corsets

The move away from corsets was driven by several factors. As long dresses went out of fashion and societal norms evolved in the late 1800s, corsets became less compatible with the changing styles. At the same time, the growing female suffrage movement, while not directly opposing corsetry, spurred the formation of subgroups that increasingly rejected the physical and emotional restrictions of corsets (Rockliff-Steiin, 2011).

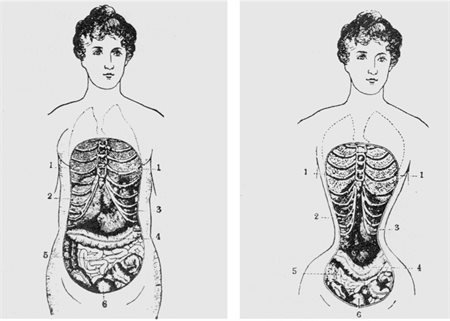

A (biologically inaccurate) image of a corset's impact on the body. Image Credit: Mel Davis (Please see the list of references at the bottom).

A (biologically inaccurate) image of a corset's impact on the body. Image Credit: Mel Davis (Please see the list of references at the bottom).

In 1881, the Rational Dress Society emerged as part of a larger Victorian dress reform movement, which condemned any clothing that altered or deformed the body. This included corsets, high heels, and heavy skirts. The Society advocated for clothing that promoted health, comfort, and beauty, without compromising women's well-being.

Their exhibition slogan- "grace and beauty combined with comfort and convenience” emphasised that fashion should not perpetuate harmful standards of female health (Evening Journal, 1888, p.3). This movement did not reject the desire for beauty but sought clothing that was free from physical harm.

Charlotte Stopes, a key figure in the movement, gained significant attention after an impromptu session on rational dress, which received extensive media coverage. Though she advocated for comfort, she did so within the limits of Victorian standards of modesty and propriety.

Her approach was subtle and effective, challenging societal norms without causing a dramatic backlash, or incurring a reputation that could automatically brand her a source of ridicule.

Interestingly, Oscar Wilde, a well-known figure in queer philosophy, also contributed to the discourse on dress, emphasising the relationship between clothing and the soul. His ideas resonate with contemporary concepts of personal expression through fashion. On a more practical level, the Anti-Corset League criticized corsets for their detrimental effects on women's health. Dr. Herbert Snow, in particular, argued that corsets were linked to cancer. While this claim was likely influenced by the industrial revolution and lifestyle changes, rather than any direct causation from ‘the civilised nations’ that wore corsets, it contributed to a growing fear of restrictive clothing (Isaac, 2017).

This fear, combined with the anti-restrictive movements and arguments for less rigid gender distinctions in dress, gradually led to the decline of corsetry as a fashion staple and the height of innovation.

Dr. Herbert Snow was more extreme in his views of corsetry than most, arguing that “if ladies only knew how ridiculous they made themselves appear in the eyes of the baser animal man by wearing corsets, he felt sure they would soon abandon the absolutely sickening features they now presented” (Evening Journal, 24.11.1888).

This echoes modern beauty standards that prioritize unattainable, often unhealthy body types. These trends, like the obsession with the taut and emaciated body in the early 2000s, reveal a cycle of harmful fashion ideals that transcend eras.

Dr. Snow’s criticism suggests how society's fixation on body image can go beyond mere trends, shaping an identity that is often both unhealthy and unrealistic.

It highlights the ultimate irony- that this gruelling process of self-regiment and deprivation is actually opposing the male idea anyway. In this way, Snow’s admission that women were trying to appeal to men, but were effectively doing it wrong, demonstrates the contradictory standards of the self that women are often held to.

This idea of reforming corsetry needed to be a gradual process. Snow argued that abruptly removing the corset would cause irreversible damage to the spine, and the 'reformed woman would gain little benefit from her newfound freedom' (Evening Journal, 24.11.1888). Instead, change should occur incrementally, allowing people to adjust to new norms without reverting to old habits.

This idea reflects broader societal change- where too much radicalism, even with the best of intentions, can have harmful consequences. Physically it highlights how trends are all-consuming, and we are only able to see the extent of the damage when we take a step back, and realise it is too late.

True reform happens slowly, with people gradually accepting new ways of thinking and living, as seen in the shift from restrictive corsetry to more comfortable clothing- metaphorically and physically loosening the constrictive binds on the female body.

Civilian Clothing 1941 (CC41): The war on the Home Front, and on the female image

One of the physical incentives for more adaptable dress-ware was the emergence of women into previously male domains. With the Second World War conscripting the majority of the male workforce, and an increasing risk of technological and economic collapse, women were actively encouraged to engage in physical and intellectual labour, in a way that was previously reserved for men - or the working-class. By the 40s, Civilian Clothing 1941 (CC41) clothing came into effect, commissioned by the government under an initiative by Winston Churchill. Assumed to stand for ‘Civilian Clothing’, and implemented in 1941, CC41 clothing was a way of meeting the demand for dress ware, in a way that was sustainable, and in line with the rationed cloth available. This was clothing uniformly branded with the CC41 stamp, with simple skirt patterns, or more significantly, trousers.

In contrast to the late 1800s, when clothing often served as a representation of one’s social status and estate, the 1940s saw fashion as a reflection of national unity and collective pride. Churchill himself argued that if the visual standards of the nation faltered, so too would the morale of its people. This perspective mirrors the previous century where clothing signified status, but now it also underscored the broader theme of national survival. However, the role of women in this shift is far more complex than simply ‘liberation.’ Even as women gained access to new roles and more practical, less performative, attire, questions surrounding autonomy and expression remained.

Firstly, women were seated in male roles, that were previously inaccessible. There had been this long-standing belief that women weren’t just responsible for raising the children, but instead they were not employable at all, physically and emotionally incapable of high standing positions, like being a doctor or a scientist.

This is witnessed by the general omission of women within universities, until it became more mainstream in the mid 20th C. The war provided a landscape of economic desperation - women were required to make a sustainable Britain for the soldiers to return to.

Despite the hardships of the war, women played a critical role in keeping Britain functional - managing everything from rationing to maintaining supply chains during a time of global economic crisis.

The wartime necessity of women stepping into these positions demonstrated that there were no inherent physical or intellectual limitations preventing women from taking on such responsibilities. This, coupled with ensuing post-war economic crises, created a landscape where women were not only wanting to work, but were now given jobs with power, prestige and influence.

Beyond this, the war reshaped class divisions- a notable change from the 1800s. Women from all backgrounds were called upon to contribute to their communities, often stepping beyond their traditional roles. Working-class women found themselves taking on supervisory roles, such as managing local shops or operating typewriters in administrative offices. This reshaping of class norms provided a collective identity for women that transcended their social standing. Under the pressure of wartime necessity, the traditional barriers of lineage and status began to blur.

This subversion of class norms merged a rigid part of identity, again unifying women under a more complex umbrella term, as Churchill’s moral comraderies- rather than separated by lineage and social standing. This paradigm-shift questioned fundamental beliefs in terms of worth, social standing, and suitability. In a way, this provided a sense of governance on destiny - it highlighted that women were in fact capable of roles outside the home- and in the same way there seemed to be no innate difference between genders, neither was this innate capability between classes; to a degree, this wartime desperation forced individuals to address their similarities in identity and personal experience, despite different lived experiences as both the oppressor and oppressed.

The clothing worn by women who took on more physical, labour-intensive work during the war reflected this shift. With rationed fabrics, traditional gendered clothing markers (like skirts and dresses) became impractical. In their place were more simple skirts, or trousers similar to those worn by men. This allowed women to holistically immerse themselves in the workforce, physically, politically, and socially.

The psychological impact of fluid clothing

A key question to pose here is this:

- Was the physical insertion into male apparel a form of embracing the egoic mind, and the non-binaries of clothing - or was it a psychological barrier, that actually separated the war effort woman, from feeling the ownership over their contribution?

By this I mean - does the act of wearing the trousers, both figuratively and literally here, emancipate women only on the grounds they are mirroring their male counterparts, rather than truly demonstrating their own capabilities (De Merteuil, 2020). For some, the physical emulation of everything they were told they could not access must have been empowering, symbolising freedom and autonomy.

For others, however, it may have mentally represented a temporary departure from traditional gender roles, necessary only for the duration of the war. The post-war shift in women’s fashion - when some women were able to maintain this rejection of traditional femininity - contributed to the later anti-fashion movements of the 1970s, which challenged conventional gendered norms in dress and expression with a more fluid relationship between gendered clothing.

The changing attitudes towards the petticoat and CC41 trousers demonstrate the progression of inner dialect and identity. The relationship between clothing and self-expression is not just about the garments themselves but the context in which they are worn. For women in the 1800s, clothing like the corset served as a subtle marker of identity, signalling one’s social class and femininity.

By the 1940s, the more overt shift to trousers demonstrated a physical and social liberation that defied traditional gender norms. This evolution highlights the changing nature of gender roles and the ways in which clothing can both reflect and shape our understanding of identity. Women started with subtle clothing choices often unnoticed by the opposite sex, or those beyond their social class.

The petticoats’ subtle alterations, enhancements and ultimately the curated image demonstrated the fragility of identity and expressionism within the 1800s; the more overt male parallels with CC41 trousers demonstrated how these hesitancies and subtleties were overwritten. Women transgressed the distinction between classes, and between the sexes, an overt, and significantly, collective form of liberation that actively defied the male-gaze, rather than perpetuating general subjugation, at the hands of small individual acts of liberation or control.

In this sense, both the corset and the CC41 trousers embody the broader social changes of their respective times. The restrictive nature of the corset represented the suppression of women’s autonomy, whereas the wartime trousers symbolise a more radical break from traditional gender expectations. Women’s experiences with clothing- whether in the form of resistance or adaptation- offer insight into the ongoing struggle for self-expression and social recognition.

The changes demonstrate the progression of clothing and its relationship with identity, in line with societal opinions on sexuality, femininity and liberation. With the emancipation movement, the dialogue of female suppression, angst and competition previously encapsulated by the corset, became more overt and vocalised. Both the petticoat and CC41 converge on the same idea - our understanding of our own identity and place in the world is deeply seated in fighting the suppression of the self, the safety in dissuasion from the norm, and our ability to express ourselves through our language, behaviour, and appearance.

The relationship between fashion, identity, and societal norms continues to evolve, with each generation redefining what it means to express individuality in a world that often seeks to impose conformity. Ultimately, whether it is the subliminal codlings of the 1800s petticoat or the more overt shift to CC41 trousers, the history of women’s clothing emulates the battles of resistance, liberation and subjugation. The complexities of identity within differing social expectations demonstrates how clothing remains a powerful tool in the expression of gender, identity, and self-expression.

References

- Aspinall, H. (2012). The Fetishization and Objectification of the Female Body in Victorian Culture - Arts and Culture. [online] Brighton.ac.uk. Available at: http://arts.brighton.ac.uk/projects/brightonline/issue-number-two/the-fetishization-and-objectification-of-the-female-body-in-victorian-culture.

- Cunningham, Patricia A. (2003). Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850 – 1920: Politics, Health, and Art. Ohio: Kent State University Press.

- Davies, Mel (1982). Corsets and Conception: Fashion and Demographic Trends in the Nineteenth Century. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 24(4):611-641.

- Kunzle, David (1982). Fashion and Fetishism: A Social History of the Corset, Tight-Lacing, and Other Forms of Body-Sculpture in the West. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Marcus, Stephen (2009). The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-Nineteenth Century England. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

- McClintock, Anne (1995). Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge.Morag, H. (2010). Queering the Corset. The Skinny. Available at: Theskinny.co.uk.

- Mulvey, Laura (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3): 6–18.

- Pereira, R.S.P. (2020). The Corset as a Fetish Object of Victorian England and the Crisis of Values into the Dynamics between Class and Gender. ModaPalavra e-periódico, [online] 13(29): 43–69.

- Rockliff-Steiin, Consuelo Marie (2011). Pre-Raphaelite Ideals and Artistic Dress. Gilded Lily Publishing. 30 September 2011.

- Steele, Valerie (1996). Fetish: Fashion, Sex and Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Steele, Valerie (2001). The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Steele, Valerie (2004). Femme Fatale: Fashion and Visual Culture in Fin-de-siecle Paris. Fashion Theory, 8(3): 315-328.

- Stanchieri, M. (2023). There is Nothing More Traditional than a Man Wearing a Corset. [online] nss magazine. Available at: https://www.nssmag.com/en/fashion/32167/history-men-corsets.

- Summers, Julie (2015). Fashion on the Ration: Style in the Second World War. London: Profile Books.

- Walsh, S. (2019). Straight-Laced: How the Corset Shaped Turn-of-the-Century English Femininity. [online] Available at: https://crimsonhistorical.ua.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Straight-Laced-PDF.pdf.